What Indigenous Designers Want (and Need) Out of Fashion Collaborations: A Guide for Brands – Latest Fashion Trends & Style Tips June 12, 2025 at 06:15PM

📰 What Indigenous Designers Want (and Need) Out of Fashion Collaborations: A Guide for Brands

✨ Fashion Insights & Trends:

Fashion's long history of cultural appropriation is common knowledge at this point, and in North America, Indigenous communities have been among the most brazenly exploited by the industry. Even today, the American Western aesthetic has exploded into a massive fashion trend, with little regard for its Indigenous (and Black and Latinx) roots.

In particular, Native-"inspired" prints (often with ill-defined descriptors like "Navajo" and "Aztec") have been appropriated by too many non-Native fashion brands to count. Meanwhile, contemporary Indigenous artists and designers — people whose ancestors were making clothes and jewelry long before European colonizers set foot on their land — have had their progress slowed by years of systemic marginalization and inadequate industry support.

Despite centuries of attempted erasure, these communities are bold and resilient, and making contributions to the modern fashion industry that deserve recognition. And perhaps they are starting to get it; Designer Jamie Okuma, who identifies as Shoshone-Bannock, Wailaki and Okinawan, became the first Native American inducted into the CFDA in 2023. And as of last week, she's the first to become a finalist for the prestigious CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund.

Meanwhile, from prominent brands, we're starting to see fewer instances of appropriation and more instances of collaboration, from Ralph Lauren's Artist in Residence program, to Arc'teryx's Walk Gently initiative.

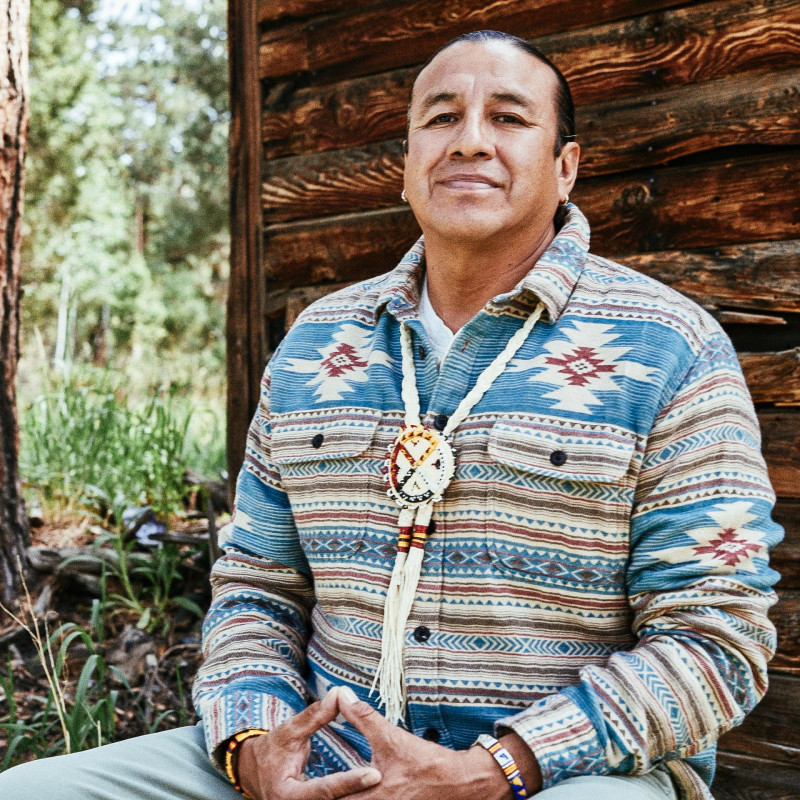

Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Lauren

If progress is going to be made, it's important for culprits of Native appropriation to make public apologies and efforts to invest in the communities they stole from — and perhaps no one has done this as well as Faherty, a New York-based, family-run casual apparel brand founded in 2013. The B Corp-certified company's holistic approach to Native partnerships, developed and guided by Native people, has evolved into something of a blueprint for how to effectively and authentically collaborate with and invest in indigenous talent.

Of course, mainstream success and acceptance by traditional industry gatekeepers are not the goals of every Indigenous designer. But there is a lot that established brands and can do to platform and uplift native talent, especially by eschewing appropriation in favor of collaboration. That is, if it's done right.

"For change to happen, we have to have big brands at a global level be on board with saying, 'we can't exploit people anymore,' or, 'we can't just take without giving proper credit and investment to communities that this cultural art comes from,'" says Bethany Yellowtail, founder and designer of B. Yellowtail and one of Faherty's designer partners. (She's a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe and a descendant of the Crow Tribe.)

In addition to Yellowtail, we spoke with Faherty's Co-founder and Chief Impact Officer Kerry Docherty and other Indigenous designers to share a few guidelines on how brands can get these partnerships right.

Don't Let Fear Get in the Way

This goes for any effort to engage or collaborate with people from marginalized communities with whom a brand might not be familiar.

"I think there's so much fear in the fashion industry about being called out or doing something wrong, and that fear can prevent progress," observes Docherty. "I think there's so much opportunity, I just hope that the fear in doing it wrong doesn't prevent them from actually forming these types of relationships."

She advises brands to start by listening and learning: "Increase your education as to as many different Native issues, causes, nonprofits, artists as you can. If it's Instagram, fill your Instagram feed, sit and learn and watch, observe. It's the first step."

Take Responsibility

Photo: Courtesy of Faherty

We don't often see brands take accountability for cultural appropriation before being publicly called out for it, but that's what Faherty did in 2017 when it published an apology on its website for using Native patterns.

"For us, it was less about being called out by customers or by other people, and more of an internal reckoning of looking at our Native-inspired prints and realizing that these prints did not belong to us. And while they were objectively beautiful, to use them without giving any resources back to the Native community felt like a form of exploitation," explains Docherty, whose background in social justice law was no doubt a factor in her thoughtful approach. "[Native-inspired patterns represented] a small percentage of our business, probably around 10%, maybe less. But we had to make the decision: Do we not want to use these prints at all or do we actually want to work with Native artists and Native designers in a mutually reciprocal relationship that benefits them?"

The company took the latter route, and this initiative has evolved into a benchmark for how Native artists and non-Native companies can work together. But it took time to get there.

"So much of it is showing up with vulnerability and accountability," says Docherty. "The first artist who we had reached out to was through a mutual friend named Doug Good Feather. And I called him and I said, 'We have a clothing brand and we've been using Native-inspired and we don't want to do that anymore. We know it's harmful and exploitative, and we'd love to start working with artists to create their own unique prints."

While Good Feather ended up a longterm partner of Faherty's, any initial skepticism would have been understandable. "I don't want to speak on behalf of the Native community, but there's a lot of distrust, I think, in power dynamics around the white community and capitalism," says Docherty. "And so I was very focused on continuing to show up every step of the way, being honest, being transparent, letting them know, having it be an ongoing dialogue of how this could be successful. I do think for founders or other brands, there has to be a level of sensitivity and knowledge around Native erasure for it to be successful."

A collaboration with a Native artist or designer does not, on its own, count as an apology, by the way. Docherty recalls: "We have heard of bigger brands who have reached out to artists who have wanted to work with them. And the artists said, 'I would love that, but have you ever publicly apologized for past harm?'" That needs to come first.

Avoid One-Off Marketing Plays

Photo: Courtesy of Faherty

Yellowtail immediately pointed to Docherty's forthright and committed approach as a main reason she was interested in working with Faherty: "I just really loved how candid she was about it and just like, 'Yeah, we messed up. We shouldn't have done that, and now we want to make it right — and not just make it right. We want to create meaningful partnerships.'"

A one-off collaboration or campaign executed by a marketing team can come across as surface-level virtue signaling at best, and another form of exploitation at worst. Ongoing partnerships not only feel more authentic to consumers, but they also can have a real impact on participating talent and their broader communities, as well as consumer mindsets.

Faherty's approach was to launch a holistic Native Partnership Program, which involves ongoing collaborations with five Native designers, with whom it puts out more than 50 co-created products annually. These partnerships include design fees, royalties, inventory sharing, business support and even donations to Native-led nonprofits. Eight years in, the program is still going strong.

Part of making longterm partnerships work is flexibility: "It's really fluid, so sometimes it's seasonal, sometimes it's yearly. It depends on their bandwidth, too," says Docherty. It's also crucial to continue on the right path long after you start.

"We may be the one time that [a brand] works with a Native artist, but the company may still go on and create culturally appropriated designs and motifs," notes Lauren Good Day, an Arikara, Hidatsa, Blackfeet and Plains Cree artist and fashion designer from the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota. "Continuing the collaboration, and cutting off the culturally appropriated designs — I think that's what solidifies for me what an appropriate collaboration would be."

Make it a Company-Wide Mindset Shift

Photo: Courtesy of Faherty

Of course, collaborations alone may not fix the issues within a company that led to instances of cultural appropriation in the first place. Collaborations are often handled solely by marketing teams, but combatting ignorance should be a company-wide endeavor.

"I think the best part of our collaboration when we first began, is they actually had me come in and speak to their whole headquarters," says Yellowtail." There's this internal piece that I don't think happens with larger companies… because it's really a mind shift and a cultural shift within the company that has to happen."

Docherty adds: "Having our team hear these stories around Native erasure, around conversations like genocide, around what the Native community is currently facing still, I think helps the team treat these type of partnerships with more care."

Beyond education, hiring people with diverse perspectives is also crucial to making these types of initiatives work. "You should ensure that you have Indigenous people on your team," advises Docherty. "There should be adequate representation at the board level, encouraging it to be more than just a marketing plan." As part of its efforts, Faherty brought on Crystal Echo Hawk as a board member and Lisa Diegel (a Nisga'a Nation citizen) as its head of sustainability.

"We are an American heritage brand. That's how we're very much described, aesthetically, and America includes the Native community, and I think the Indigenous population is at the forefront of climate change," Docherty adds. "There comes a deeper understanding and wisdom in their lived experience that is such a gift to our team."

Understand Ownership, Permission and Context in Native Art

Photo: Courtesy of Faherty

Many of the prints and motifs that Indigenous artists incorporate into their work are rooted in tribal traditions — their historical and cultural significance means they can't simply be licensed to non-Native companies in the way that other types of art can, hence why appropriating them without any permission at all can be so harmful.

"Our designs are attached to who we are as people, to the land we come from, our ancestors," says Yellowtail. "If you're not willing to invest in that, then maybe you should go get inspired somewhere else."

In no way can a brand have ownership over another Native artist's print, and this should be clarified when collaboration contracts are developed. Michelle Brown, creative director of Eighth Generation, a Seattle-based lifestyle brand that partners with Native artists across the country, explained this during a panel discussion at Native Fashion Week Santa Fe (NFWSF) in May 2025. "Beyond just paying royalties or licensing the art, the artists themselves own the artwork. They can choose not to work with us and to discontinue that partnership."

For Faherty's part, "We say, 'the artist has given us permission to use this print,'" Docherty notes. In turn, the artist receives royalties. "At the end of the season, if we wanted to run it again, we would go back to the designer and ask if we had permission to do so."

Beyond confirming permission to use the print, brands must also ensure they're using it correctly, which highlights the importance of the artist's continued involvement. At Faherty, there was an instance where its men's design team wanted to use one of Yellowtail's motifs for a men's jacket after seeing it on a women's sweater. "Bethany saw the sample, she said that motif represents fertility and we would never put that motif on a man's garment," Docherty recalls. "And it was such a good learning for our team to be like, these motifs have meanings. This is not just a pretty pattern, slap it wherever you want."

Take a Decolonized Approach

Doug Good Feather

Lehi ThunderVoice Eagle. Photos: Courtesy of Faherty

Clarifying who owns what and giving Native artists the power to say how a motif should or should not be used are both crucial to ensuring a decolonized relationship.

"We make sure that we have decolonized guidelines even in our contract about what this is," says Docherty. "A lot of it comes down to power dynamics and who's owning the resources and how those resources are being shared. If our mission, which it is, is to streamline as many resources as possible to the Native community, we want to make sure that we hold ourselves accountable to that mission."

For example, Faherty doesn't make its partners sign a non-compete. "If Bethany Yellowtail wants to do something with another brand the exact same season as us, I'm not going to tell her she can't do that. Good for her getting as many resources as possible."

"When it comes down to it, we want to represent ourselves… [Faherty] really leans on us for the guidance in the design process, and they're the experts in the textiles and the fabric," adds Yellowtail.

For a partnership to have a real impact, it also needs to align with and support the Native designer's goal or mission for their own business. At Eighth Generation, artists are also able to wholesale their collaborative products through their own sales channels. ("Our artists are entrepreneurs at the end of the day," Brown notes.) Faherty offers this as well. It will also change payment plans, offer loans, provide factory contacts and share retail space with its partners based on their needs, as part of its mission to invest in Native communities.

"I would love to get to the point, and this is probably years away, where we don't even have to do these collaborations, that the brands and partners that we work with are so established on their own that we can actually just buy product from them and share it on our site," says Docherty.

Reframe 'Success'

Photo: Courtesy of Faherty

Many of today's Native founders incorporate traditional crafts and techniques, passed down from their ancestors, into their otherwise contemporary work.

"It's such an important part of our actual tribal economy — making making craft or making bead work, making items and using that as a form of commerce. That's been a part of who we are since time immemorial," says Yellowtail. "Now where we're at, we're seeing how it could be careers and be people's family livelihoods, because [consumers] want it."

But regardless of the quality and authenticity of their work, most fledgling Indigenous designers lack the resources to scale and build a viable business on their own, which is why collaborations between them and larger non-Native companies are needed to fuel growth within the Indigenous fashion industry.

"The tribal community I come from has 70% unemployment rate. And so I imagine what something like a billion-dollar fashion industry business that always profits off Native design could do in partnering with our communities and doing well by the people that it comes from," says Yellowtail.

Of course, companies stand to benefit from these partnerships, too, though they may do well to expand their definitions of success beyond sales and good press. At Faherty, for instance, these initiatives have made the company more attractive to talent.

"The number one reason when people come to work at Faherty is around our commitment to sustainability and our Native initiatives program, which I think goes to show the desire for people in fashion to have something that feels more meaningful beyond the selling and making of clothes," Docherty says. "How my friends and these fellow artists, how they make decisions for their brand and for their community, is so centered on what they can give back. That has given me such a fresh perspective on what it means to allocate resources and really what success can mean beyond just the act of having a big clothing brand."

She's eager for other fashion brands to adopt similar models, and is happy to help. "If any fashion brand wanted to reach out and be like, 'how are you guys doing this? How is it working? Do you have people you can connect us to?' Yes. Amazing. This is not proprietary information, this is just around mutual respect and progress."

📌 Love fashion? Follow us for daily updates on our fashion blog! 🌟

🔹 #FashionTrends #StyleTips #OOTD #What Indigenous Designers Want (and Need) Out of Fashion Collaborations: A Guide for Brands

Comments

Post a Comment